It was during a Permanent Way Institution visit, in June, 1989, hosted by British Airways, that the scout vowed to go back to see more of what became Heathrow (after the farm) in 1966; for, even though he would gladly force, if he could, aviation back to the days of his boyhood, when only one in 600 people had flown, he is to this day fascinated by the technology and spectacle; his father had once come home with a BOAC shoulder bag, proving that he knew someone who had travelled this way.

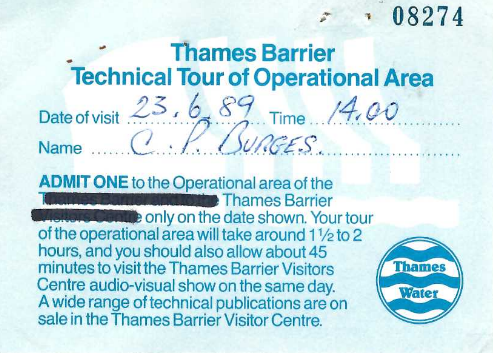

The secretary who organized the visit was the late Peter Haigh, who at the time was taking flying lessons. P.W.I. trips were laden with fun and interest. This one involved an overnight stay in London, where the scout was mistaken for Timothy Dalton (the then Bond) in a nightclub, and visits to the London Underground control and regulating room at Earl’s Court, and Lillie Bridge track maintenance depot, followed by a tour of the Thames Barrier, including a walk through the service tunnel beneath the river.

After arriving at Hatton Cross Station, the scout vaguely remembers the party taking lunch at a pub frequented by airline staff, including heavily made-up hostesses with perfectly coiffed hair, chattering about exotic places; holiday destinations for most, but merely stopovers for these ladies.

At some point, a B.A. coach collected the party and took it to a Heathrow office for a film show and thence to a hangar, where a Concorde and Boeing 747 were “on shed.” Members were escorted onto both aeroplanes; upstairs and into the cockpit of the Jumbo, with a peek at the “mile-high” compartment; and into the comparative confines of the supersonic.

Here, the host regaled the party with facts and figures: the fantastic cost of components like windscreens and seats; that in flight the aircraft grew six inches longer due to air friction. He pointed to the “Mach 1/2” indicator on the bulkhead and a wag in the group likened it to the E. & T.V.R. utilicon.

Just 18 years later, in August, 2007, the scout boarded an Adelante D.M.U. at St. David’s; the guard had had to unlock the bike space with his carriage key and would have to remember to do the same at Reading.

A Turbo took the scout on to West Drayton, from where he rode along some wide bicycle lanes, then rare in Devon, through the village of Sipson to Heathrow.

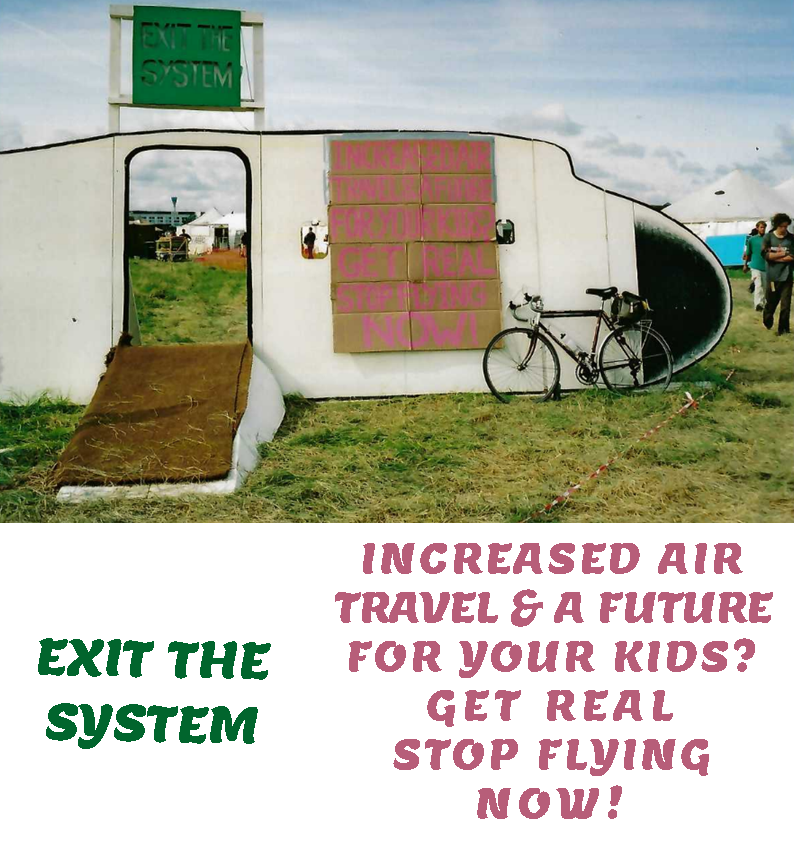

It so happened that a protest was being held about the plans to build a third runway and it was to the site of this that the scout went first. He toured the encampment, made a donation and came away with a great bundle of leaflets.

Amusement came from career protesters sending apologies for their absence from such as South America and an airline boss questioning: “And how did they get there? On the bus?”

Metropolitan Police attended in strength: officers were on foot and horseback, and in vans and a helicopter. The scout asked two friendly-looking constables if they knew where to find the viewing area used by planespotters. They did not and the scout was later told that it had been closed.

There are smaller tunnels on either side of the main road tunnels beneath the northern runway, supposedly reserved for taxis, through which it was possible to walk or cycle. There were humps at regular intervals but these had gaps, enabling cyclists to outpace cars.

The scout emerged from the long tunnel like a shot from a gun and wandered around the terminal complex, pushing his bike. He asked a security man if there was anywhere he could leave his bike and was told: “Best keep it with you, Sir.” Even with heightened tension, the scout did not arouse suspicion, showing that some people can remain inconspicuous. In all the commotion, and having got quite lost among the snaking queues, the scout began to think that he may have had to go to New York and back just to get out.

There was no one on a high platform to lead the scout from the maze but, eventually, following the usual routine of climbing over barriers and ignoring the traffic signage, which so constrain the “liberated” motorist, he found his way to the exit tunnel and the perimeter road – actually called Perimeter Road, with points of the compass prefixes.

It is nine miles around and, confusingly, has two McDonald’s. Chain hotels – with rooms identical the world over – offices and distribution sheds line the route, sprinkled with traditional buildings, including pubs which could have been the haunt of World War II fliers; in fact, none was based here. It was at one of these that the scout stopped for lunch.

It was impossible to become disorientated because of the east-west alignment of the runways and the queue of aircraft over London waiting to land.

The scout dwelt for a moment on Eastern Perimeter Road to assess the planespotters positioned on some grass and concluded that they were of a higher calibre than the spotters once seen on station platforms.

On Southern Perimeter Road, a B.A.A. worker had lit up and the scout preyed upon him for a gasper. The man had not only to leave the enormous premises (it is said that the land required for the new London and Birmingham railway will be less than the size of this airport), he had also to get out of his van. He explained some of the workings of the airport: headways, stacking, swapping runways, night flying, etc. He told the scout that there were once plans to flood the site for flying boats but the scribe has not been able to find mention of this.

Completing the circumference, the scout stopped on Northern Perimeter Road to marvel at planes taking off, after the switch to runway 27R in the afternoon. He noticed one copilot appear to observe the windsock.

A little fuel comes by rail along the former Staines & West Drayton line to a terminal at Colnbrook.

The scout then rode the few miles to Hayes & Harlington on the G.W. main line. A little beyond the station, he joined the Grand Union Canal, soon turning north onto the 13½-mile Paddington Arm. This goes north to Greenford before turning east and is part of a 27-mile “pound,” or open water between locks.

The scout stopped at Willow Tree Footbridge to take in the contrast with what he had seen earlier.

While on the Stonebridge Park Aqueduct, the scout looked from his tranquil transport route at the manic movement on the expansive North Circular Road below.

Never forgetting that these waterways were the freight transport arteries of their age, the scout was heartened to come upon a new wharf. Beside the bridge carrying the North & South Western Junction Railway stood a sign proclaiming: “New Wharf Construction” at “Old Oak Sidings.” “New infrastructure to promote [carriage of freight by] canal” was the initiative of British Waterways, Transport for London and Powerday, a waste management and recycling firm.

Then came Little Venice, the junction of the Regent’s Canal, where a convivial atmosphere was felt on this Saturday evening, with boat people cooking their dinners or drinking cocktails. The canal was certainly the most pleasant, if not the most direct, way of getting into London.

From the Paddington Basin it is but a short distance to the station, where the scout put his bike in the first available H.S.T. Less than ten minutes after departing, while standing in the bar car, he saw Hayes & Harlington flash past the window.

All the while he had been at the airport, including his tour of the protest camp, he had thought that an empty space had been reserved for the proposed third runway. It was only later that he discovered where this would be built: Sipson, the village he had cycled through. In all, 900 homes would have to be demolished.

During the 2020 plague, Heathrow operated only one runway and there was talk of reduced flying in future, but expansion of the airport is still actively being pursued in 2021.