This was a case of very short-term planning. The scout had passed through the barrier at St. David’s intending to catch the 1025 to Sidmouth Junction when he heard announced ” … Waterloo cancelled.” The scout’s hesitation was broken by the 1019 to Barnstaple Junction running into three and soon he found himself heading north, not east, with vague thoughts about possible rides without a map.

He still hadn’t made up his mind as the train sped through Lapford, but by the time it slowed for Eggesford he had plumped for a ride to Witheridge and Tiverton.

The 1036 Barnstaple was running late and so the guard was collared for a quick chat. With reports of much reduced ticket issues at booking offices, the scout was curious about on-train sales. The guard, new to the job, reckoned that around 70% of passengers pre-booked.

When the scout made his regular ride along the North Devon turnpike in June, he was happy to be “off duty.” He did, however, fetch the railway’s Cybershot out of his saddlebag for this composure.

He had been passed on the turnpike by a police car, a rare occurrence; he thought he had seen “B.T.P.” (British Transport Police) in small lettering on the back, which would have made the sighting rarer still. When he got to Eggesford, the scout saw the car at the front of the station, which is just off the road. He wandered into the old goods yard and when he returned to the frontage the Railway Police car had gone.

As on other occasions, he made for the shade of the Down platform, where to eat his lunch. Glancing left on the crossing he muttered to himself: “There’s one for the library.” He put his bike by a fence and positioned himself just over the solid white line on the rubbery crossing unit in the “four-foot.” Seconds later, he heard a horn. When it sounded again, he looked around and saw that the police car had reappeared and was waiting at the junction of the Witheridge road. The driver was waving wildly.

A photographer could have been startled by this and stepped back into the path of a road vehicle. The scout merely groaned and waited for the car to stop just off the crossing. Approaching the scout, the constable asked, “Was it just about the photograph, Sir?” The scout resisted the temptation to reply, “No. I was actually about to plant a bomb,” and pleaded that his eye had been caught by the rhododendron in flower. The constable went to look along the line to check that there was indeed a rhododendron; remarkably, buddleia, almost the national symbol of Network Rail, was absent from the scene.

The scout humbly confessed that he should have known better but still doesn’t know why his harmless action could not just have been ignored. He did discover that police had been summoned because a passenger had collapsed on the platform.

Now, if the scribe became aware that more than a few people read these rambling pieces, he would stop drawing attention to the wonderfully empty and scenic roads that the scout has the good fortune to pedal along, often without seeing another cyclist or pedestrian.

The road to Witheridge, via Chawleigh, is a favourite. It makes an even ascent from the Taw Valley and then gently undulates across a high plateau from where there are glorious views south. It was much fresher than on previous rides this summer and so the going was easy.

Just as the scout had thought that he was again on his own, he spotted a cyclist ahead. He was hauling a trailer and so the scout soon caught up with him, calling out “Hey!” as he overtook. A hundred yards further on, the scout stopped, put his bike in the verge and stepped into the road; he had sensed that the fellow and his rig were too interesting to leave behind. He was not mistaken.

“May I take a photograph?” opened the scout. He had only been thinking that he would get to Witheridge earlier than his customary lunchtime. There followed what must have been a half-hour conversation which nicely filled the gap.

Glen, like the scout, loathes cars and goes everywhere on various bicycles (unlike the scout), including his place in the mountains of Portugal, where he winters. He was riding from Okehampton to his home in Witheridge, with his dog in the trailer and music playing from the bag on his handlebars. The rig he had put together from bits he had found at the dump. The bike had very low gears but no electric motor. Glen said that at the age of sixty he felt better than ever.

After a discussion of the snares and delusions of car ownerhip, the joys of cycling, the direction of transport in general and much else besides, the scout shook Glen’s hand and said that it had been a pleasure talking to him.

The scout rode ahead and came out of the shop in Witheridge, having bought his lunch, in time to catch Glen’s wave as he rode across The Square. If the day had gone to plan, the scout would have been around Tipton, following the Sidmouth Branch.

The scout ate his lunch and read the paper seated on a bench beside the village stocks. Not for the first time, he watched huge tractors, driven by oversexed contractors’ boys, racing past. A lorry coming from Tiverton pulled up for an oncoming tractor whose mirrors caught the lorry’s mirrors and slammed them back against the door. The driver opened the door, looked back and shook his fist, before righting the mirrors and proceeding.

The double-decker forming the 155 bus, the 1200 Exeter to Barnstaple, via Tiverton and South Molton, pulled in to its stop. One passenger got off and one boarded, the only one the scout could see when the bus passed the church. Incredibly, the 155, with its possible 82 stops, takes two hours and nine minutes from Exeter to Barnstaple. The 1214 train from Exeter Central, with its eight intermediate stops, takes one hour and fourteen minutes.

After lunch, the scout went into the church and then wandered around the village, trying to imagine it before the coming of motor transport and general modernization. Seemingly untouched little pockets helped him to see into the past. The scout had been at prep with the son of the village baker, Reed & Son. The shop closed in 2003, bringing an end to over 200 years of baking on the same site in West Street. Both the scout and the baker’s son boarded at a school less than 15 miles from their homes. They would return home on exeat twice each term.

October, 2023: While on the same ride, the scout learnt from a lady at the door of her house on The Square that Reed’s Bakery continues at premises in Chivenor, alongside the Ilfracombe line.

Except for letting traffic go past, the scout rode non-stop to Tiverton, where he wandered along the Exe, through The Walronds and the part of the town that would have been well served by West Exe Halt, had the railway remained open. He followed the road to the housing estate built on the site and in the grounds of Howden House, which the scout remembered when it was derelict. It adjoined Howden Court, the scout’s prep school, with its beautiful Georgian house and every feature of a compact country estate.

The scout then drifted back into the town, which looked drab even in the sun. Had it not been for the large number of people who seem to venture out with the sole intention of finding somewhere to eat, the place would have been lifeless. He didn’t linger long.

The Grand Western Canal had been disused for 45 years when the cub scout was taken to the far end with a group of boys and made to walk back to Tiverton as part of the local “Save the Canal” campaign, which led Devon County Council to take on ownership from British Waterways in 1971 and eventually to designate it as a country park. The scout remembered that the school had laid on marmalade sandwiches at the basin for the weary boys’ return. The school had a canvas kayak which the scout was once able to paddle a little way from the basin, beyond which the canal was choked with weeds and unnavigable.

After inspecting the Canal Visitor Centre, opened in 2013, an experience rather ruined by a very vocal child, the scout set off along the towpath.

Just at the right moment, as no one else was near, the scout spotted the “Tivertonian” approaching as he went to pass beneath a bridge. Knowing that the horse would be some way ahead, he retreated and got ready to take some photos.

The scout took it that the horsewoman was Lauren, whom he had read about in the news. She joined the crew in 2021 after graduating from university, but not in this subject. After emerging from the bridge, she called out, “I need you to stand on the other side, Sir.” The scout, feeling a little foolish, said as she passed, “I didn’t need to be told but I understand.” She spoke briefly of people who have to be told about the rope. Working horses always have right of way on a towpath.

The rope is not attached to the bow, as the pull from there would have to be countered by the rudder. A bargee once told the scout that there is an optimum point, some way back from the bow.

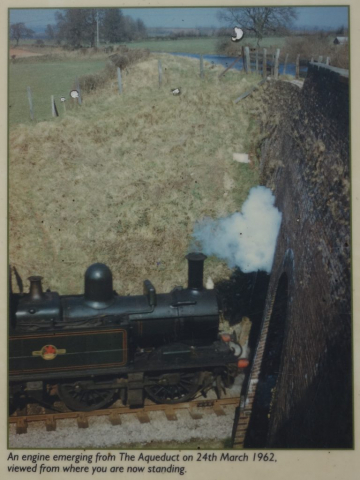

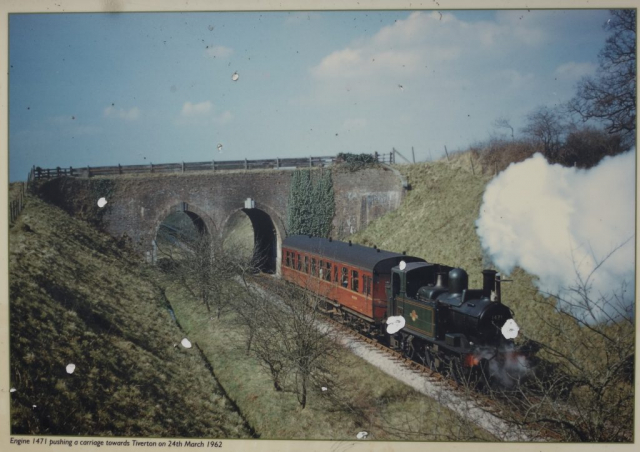

The canal crosses the former Tiverton Branch on an aqueduct. It was built with two arches to allow for doubling of the line.

The scout left the canal at Sampford Peverell and rode to the station.

October, 2023: It being a Sunday, the overspill car parks were only sprinkled with cars, but a report had reached Christow that all are nearly full on a weekday.

Sampford Peverell was one of the six stations between Taunton and Exeter where the line was quadrupled. Platform loops were installed here in 1932 as part of the Great Western Railway’s (the real G.W.R., not the fake brand) improvement works funded by interest free government loans under the Development (Loan Guarantees and Grants) Act, 1929.

With the exception of Tiverton Junction, most of the work between Taunton and Exeter was undone just over thirty years later. Sampford Peverell closed in 1964 and reopened as Tiverton Parkway in 1986, with a catchment extending to the tip of the peninsula.

This photo was taken in 2018.

There was ample time for a cup of tea and a cake before the scout caught the 1604 Paddington. He remained in the vestibule and didn’t attempt to wrestle with the other bike in the ridiculous compartment.

A young lady opened the door of her catering trolley compartment, which many passengers mistake for a toilet. The scout remarked on this and the lady agreed. She hadn’t been on the job long and didn’t remember the buffets, but said the trolleys were a bad idea; the trains were very busy on the day between two strikes. She revealed the secrets of the “Hot Water Station,” where the container in her trolley, filling about 80 paper cups, was replenished. The scout asked if she was happy in her work and if she was paid enough; he had heard that all railwaymen were on £50,000. She exclaimed that she would be a lot happier if she were paid that sum.

The scout then insisted on telling her about the stewards in white tunics who would come through the train between sittings in the dining car; one with cups and saucers taking the money and the other, following, with two large silver pots containing coffee and hot milk. British Railways, the scout went on, procured its own blend of coffee which was stored and distributed from (he thought) St. Pancras to all the railway hotels, refreshment rooms, buffets and dining cars on the system. She was probably quite glad that the scout left the train at St. David’s.

He had covered a paltry 39 miles when he got back to the utilicon.