On his first visit to Cornwall proper since 2019, the scout chose to follow one of his old routes to Newquay, crossing the scenic, but less visited, “clay country.”

He didn’t linger in town – often he used to stop for a fried breakfast – but quickly made his way towards the Trenance Valley.

There followed a very rapid descent to Nanpean, one of the least “picture-postcard” villages in Cornwall. Nearby is the birthplace of the celebrated poet and writer forever associated with “clay country.”

The scout rode through St. Dennis and down the hill to Domellick Bridge, which crosses the abandoned section of the Burngullow to St. Dennis Junction line, completed by Cornwall Minerals Railway.

Half a mile further on, the road to Indian Queens crosses the former Retew Branch. This was once hidden but now the course of the line towards the junction is a path. The scout had once ridden from Trerice Crossing to here but that path has now vanished.

A locked gate prevents access to the junction and the route goes off to cross the A30 dual carriageway, joining the old road at Toldish. Toldish Lane then beckoned and the scout followed it to see if he remembered how to get to the tunnel. He didn’t venture any further but the photos below taken some years ago are included here. Images from space show that the flooded cutting at the western end is now being infilled.

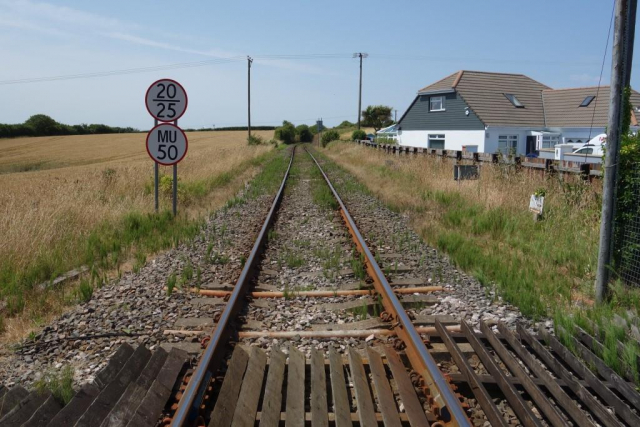

The scout turned in Indian Queens for St. Columb Road and stopped at Halloon Crossing to gaze at the weed-infested track.

Joining the busy A392, the scout enjoyed the fast ride and put up with the abuse from excited, postpubescent chaps in cars making for Newquay. At Quintrell Downs, he turned onto the B3058, as he wanted to see how Nansledan was developing.

A new clay-waste path had been made, starting next to the station entrance. It came as no surprise to find that it went all the way to Nansledan, the Duchy’s Poundbury – wickedly dubbed “Surfbury” – in Cornwall.

“I wanted Poundbury not only to be an attractive place to live and work, but also an opportunity to demonstrate that you could break the mould of conventional speculative development in the United Kingdom with its rigid zoning and soulless housing estates.” – H.R.H. The Prince of Wales, 2013

Much of the innovation of Poundbury is missing, probably because defiant car owners, who would rather go hungry than drive less, make the ideas unworkable at large. But the same craftsmen-built structures are everywhere evident.

In Newquay, it felt more like it was May or September, not high season, for the streets, in comparison with earlier years, were sparsely peopled on this warm Saturday.

Making his way back to the station for the Paddington train used to hold some anticipation. The throng having just arrived would be obvious; taxis would be loading; a queue would be forming for the departure, being hurriedly prepared by what seemed like an army of railwaymen.

Of the surviving Cornish branch termini (Gunnislake, Looe, Newquay, Falmouth and St. Ives) Newquay has been reduced the most, its three platforms (two of which could stand 15-coach trains), now only one, and that with a truncated line.

The approach was miserable and there were only a few passengers. The scout thought about all the industry self-congratulation; the thousands-strong hierarchy that reads Rail Director; the absurdity of “decorating” Okehampton with a museum-piece booking office; and of the railway made into an astronomically expensive bus service. Newquay is the decrepit, front line reality.

The Guard met the scout to tell him that the train would be terminating at Plymouth because there was no relief driver. The scout quipped that he knew the road and the Guard replied: “How hard can it be?” Anyway, the train would only have gone to Bristol Parkway, not London.

There is now only one departure on summer Saturdays (there is two on summer weekdays). The cross country operator has given up on Newquay. At least this has allowed stopping services to run, which were suspended for the most part on summer Saturdays.

The scout had reserved a bicycle space – this was his first use of a booking office since 2019 – but it didn’t seem to matter where it was stowed, as the train seemed more like an E.C.S. move to Stoke Gifford Depot.

Some of the nine coaches did load at Liskeard with beach-returns from Looe.

Each time the Guard made an announcement advising passengers that the train would terminate at Plymouth, a robotic female voice would then run through all the stations to Parkway; in an automated show of support, the moving-text screens agreed with her. The Guard advised that the onward service from Plymouth would be the 1950, the 1750 from Penzance.

On arrival at North Road, the scout found that there had been disruption. The 1837 to Cardiff and the 1850 to Paddington (1645 Penzance) were still at platforms 7 & 8. There had been a points failure outside the station and the 1850 had had to return to the platform. Then a fight had broken out and police (including a dog and its handler) was in attendance. Staff wasn’t sure what was happening. After a while, the Guard of the Cardiff, who had asked the scout to stand by, kindly returned to tell him that, due to the driver’s hours, the train would be running non-stop to Exeter. So the scout hastily boarded the London, which departed 57 minutes late.

When out for a leisurely ride and using his free travel entitlement, the scout is seldom annoyed by disruption. But there is no getting away from the realization that trains have lost most of their interest and the enjoyment has gone.