Innocent Mass-Observation of rural life in 1944

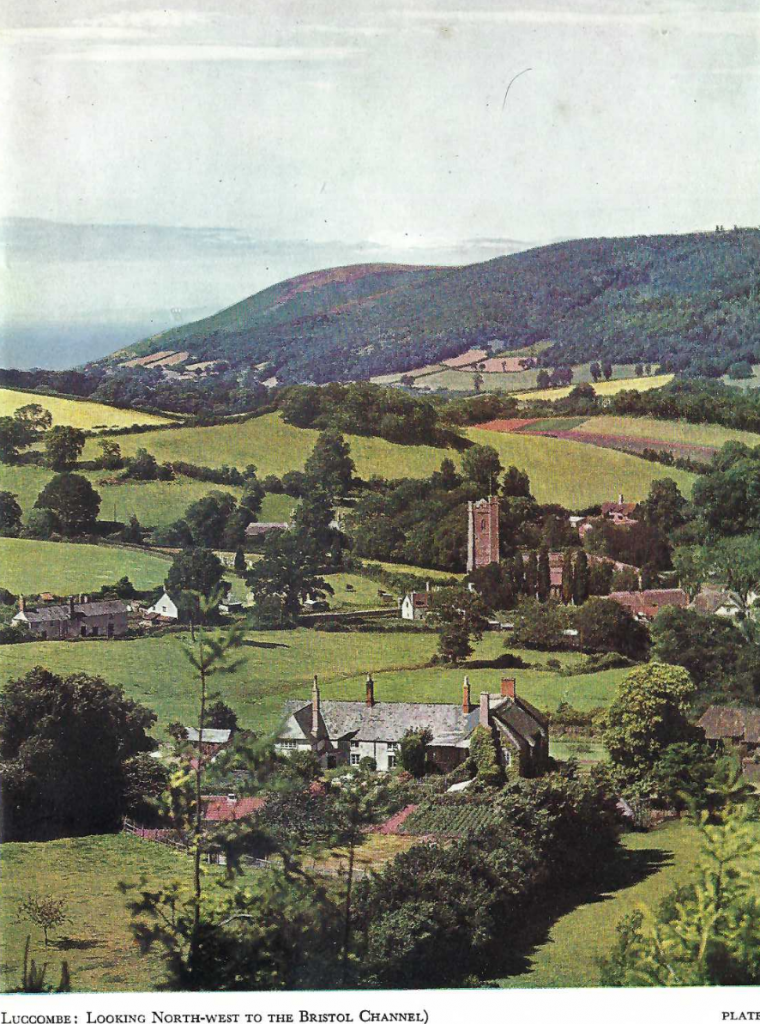

The same kind neighbour responsible for RAMBLES AROUND EXETER also loaned the scribe Exmoor Village, a distillation of what observers had recorded when they stayed in Luccombe towards the end of the war.

The scribe suggested that the scout, who had been riding to the north coast at the start of autumn for several years, take in the village in 2019.

This the scout did in mid-September, putting his bicycle on the train to Sampford Peverell, more so that he could follow a favourite route than to take a short cut.

Leaving behind the racket of the wretched trunk road to North Devon, the scout went through Uplowman and followed the juvenile River Lowman, Tiverton’s other river, to Huntsham, skirting Bampton Down to enter the town from the north-east. Then he rode over the hills to Exebridge and followed the Exe Valley turnpike, beneath the poor old Barnstaple Branch, to the summit at Wheddon Cross.

The shop assistant at the filling station where the scout has taken to buying his lunch, not for the first time asked if he’d had any fuel. “That’s it,” as he pointed to his savoury assortment on the desk, was lost on the ample local lass.

Dunkery Beacon beckoned but was still two and three-quarter miles distant. Being able to see the beacon was promising, because it meant that the climb may have been rewarded with good views, unlike the first time the scout went there, when he struggled to find the plate with pointers to the places that could be seen from the beacon on a clear day.

For the last 1,000 yards or so, the scout pushed or carried his bike up the rocky path, finally seeing the full extent of the country beyond the beacon that had been unfolding around him.

The wind was fresh to strong and it was none too warm so the scout circled the cairn before settling in what he judged to be the most sheltered spot. He was joined by a few others he’d passed on the way up.

Just as he’d folded his paper so that it would not be taken by the wind, he glimpsed a column of cyclists coming up the path now known as “Macmillan Way West.” He groaned as he remembered on another occasion the lone fellow he’d heard grunting as he neared the peak. He had dropped his bike, climbed the beacon, filmed a panorama with his phone and ridden on, barely answering the scout’s greeting.

He groaned even more when another group and then another soon became a long line heading for the beacon.

Now, it is not uncommon for the scout’s lunch hour to be delayed or interrupted at Christow by visitors who themselves do not observe regular mealtimes, or who take perverse delight in upsetting the body clocks of others, or are simply thoughtless; but having climbed under his own steam to the highest point in Somerset, a scheduled ancient monument, what should by rights be reserved for quiet contemplation, the scout was angered that his lunch break here of all places was about to be disrespected.

As the group, by now 50 or more, with their knobbly-tyred bikes and their elbow and knee protectors, buzzed like flies around the beacon, the scout turned to his fellow seekers of solitude and grumbled about their moment being ruined. He asked if anyone had a starting pistol and if he had could he trigger the riders to go away [translated].

He was told by one of the group that they had been bussed up the hill. One cast his bike down and urinated on the heather, thankfully with his back to the ladies.

When anger subsided, the scout resigned himself to the sort of people-watching he used to enjoy in the bus station caff in Exeter. He thought about how his own style of cycle rambling differed as much from what he saw here as it did from the road racing of the spandex set.

The purpose of their gathering became clear when what turned out to be an organizer scanned the wristband of a rider who promptly launched himself down a steep track. At about 30-second intervals, the others followed until they had all gone and the scout at last could enjoy the rest of his lunch.

After a few words with the organizer about the incidence of broken bones, the scout set off down the “Macmillan” path, only to meet the head of another horde going up. They could cause him no more annoyance and so the scout was happy to acknowledge their “heys.” One remarked as he approached, “rough stuff, respect,” which the scout believed may have been a reference to Rough Stuff Fellowship, a little-known off-road cycling club that was formed long before the invention of the “mountain bike.”

Much as the scout was looking forward to exploring Luccombe, he wished he could have gone back to Wheddon Cross and taken the turnpike to Dunster, a long, exhilarating descent. Instead, the drop to Chapel Cross gives up almost all the height in less than two miles, with much of it between 1:7 and 1:5. Only a daring rider will let go of the brake levers.

Passing Webber’s Post, oft referred to in Exmoor Village, more officials and off-roaders were seen, as well as a motor-quadricycle bearing a first aid symbol.

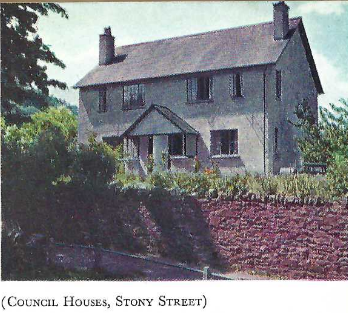

Luccombe is just around the corner from Chapel Cross and it was here that the scout remembered having gone this way before, riding via Wotton Courtenay to Dunster. So did he remember Luccombe? Not particularly, he admitted, but then Stoney Street, the most charming part of the village, doesn’t draw the cyclist.

This time the scout would dwell here and seek out the places illustrated in the book. Photostats of these he’d left back at the station so the comparison shots had to be done from memory.

British Ways of Life

Exmoor Village was published in 1947 by George G. Harrap & Co. and was edited by W.J.Turner.

It was supposed to be the first of a series of books whose intention was “to present rather more fully, and in a new manner, people and their various ways of life.”

In fact, this was the only truly rural study ever conducted by Mass-Observation, a scientific, fact-finding body, formed in 1937 to study the habits, behaviour and opinions of ordinary people.

More human than scientific, in that observers often felt rather than measured, Exmoor Village borders on the romantic in places and its somewhat idealized view could almost have been commissioned by government as “what we’re fighting for” propaganda.

Arguing that the unique diversity of the English countryside made for smallness and character, Turner writes: “It also hampers large-scale methods and the quick adoption of novelties and is favourable to conservatism, permanence and the stubborn adherence to tradition. At a time in the world’s history when we are witnessing a quick and steady deterioration in so many directions, we may be inclined to be thankful that Nature has here put a check on the tendency to degradation which exists in mankind along with the desire to improve.”

Commenting upon the huge changes that had encroached, and would encroach further, onto the village, he writes: “Few would deny the immense material benefits, yet the ordinary way of life has suffered and in some respects deteriorated. There is less character and less individuality now in the country village because there are fewer active craftsmen.”

And on the lot and standing of the countryman: “Nobody can doubt that the general dissatisfaction with what life has come to be in all its meaningless prevailing not only in England but all over Europe to-day, is a sign of a coming fundamental change. But some of the things which all men desire were once to be enjoyed more in our Exmoor village than they are anywhere in town or country to-day; and this description of things as they are in our village may throw some light on what is needed for the future.”

Exmoor Village is a valuable record of a place and a time, or a place at one time. The only purpose here is to hint at what piqued the scout’s interest without going into detail. Nevertheless, a few excerpts cannot hurt.

In the chapter on the village school, the mistress despairs that the boys just want to work on the land and the girls want to go into service. “There’s hardly one with a spark of ambition to raise themselves from the level of their parents.”

Turner replies: “It does not seem to occur to anyone that a farmer requires a different sort of education from a clerk and that it is the standardization of education that should be deplored.”

The scout and the scribe are agreed that they would happily have left school at 14 and joined the railway, equipped with all that they needed to make a start in life.

Turner, however, adopts a snobbish tone when reviewing entries left by holiday guests in a visitor’s book: “These verses are some of the less impressive results of compulsory education for all.”

In an example of children having their lessons related to what they knew, the wilderness of Scripture was one day likened to Dunkery. The next, they were asked where Jesus went after the Temptation. A boy answered: “Up on Dunkery, Miss.”

In the chapter on farming, a farmer in the village had this to say about the marketing of his spring lambs: “That’s one good thing the [National] Government has done—given us a sure market, so that if you rears a good sheep you know you’ll get a fair price for ‘un, because it’s all graded and you get what it’s worth. … But after the war what’s going to happen? That’s what I’d like to know. The town people always expects their food to be cheap. They’ve taken high prices for granted now there’s a war on, but food will be the first thing they’ll expect to buy cheaper after the war.”

The scout wonders whether today’s farmers would prefer wartime order over market fluctuations or the dictatorship of supermarket buyers.

So taken was the staff with Exmoor Village that an old copy was obtained for the station library. A pretty label stuck to the flyleaf reads: “This book belongs to Rosemary Lewis.”

That the scout was looking at scenes largely unchanged and unspoilt, save for the usual sprinkling of jarring metal crates, is largely thanks to Luccombe being part of the Holnicote Estate, gifted to the National Trust in 1944. But he was well aware that the life within the fabric of the village had changed completely in the 75 years since. When could it last have been said that all the men worked outdoors or with their hands and all the boys expected to follow them? But Turner said in his time: “It has probably changed more in the last 50 years than ever before … “

The scout is used to riding into a village and not seeing a soul or hearing a sound, even on a bright summer’s day. A fellow was working in the churchyard and a few faces were seen but this hardly excepted Luccombe from the norm. Had the scout visited in 1944, it’s unlikely that his extensive movements in the village would have gone unobserved or that he would have had no contact with villagers. But even Turner remarked: ” … although the village remains, the communal life has dwindled from what it was.”

The scout left Luccombe and rode via West Luccombe to Red Post on the busy A39. How could he not have taken a detour into Allerford?

On his way to Minehead, a lone descent-rider, separated from the pack, emerged from a lane. Now with the advantage, the scout showed what a steel frame and 117-inch top gear can do on the open road, even when powered by a semi-fossil. He shot past the dashing young blade and continued without let up for some way. This rare bout of competitiveness also caused him to shoot past three of the turnings to Minehead, but was nonetheless satisfying.

There was time to relax, drink a cold beer and watch the activity at Minehead Station before catching the train to Bishop’s Lydeard, hauled by a Manor.

The scout stuck the railway’s Cybershot out of the window and filmed the length of line covered by the Christow motor trolley and the loco barking on the climb to Washford. The seasonal service on the privately-run Minehead Branch was suspended in 2020 but it is hoped that there will be an opportunity to film again, now that the camera’s microphones have mufflers.

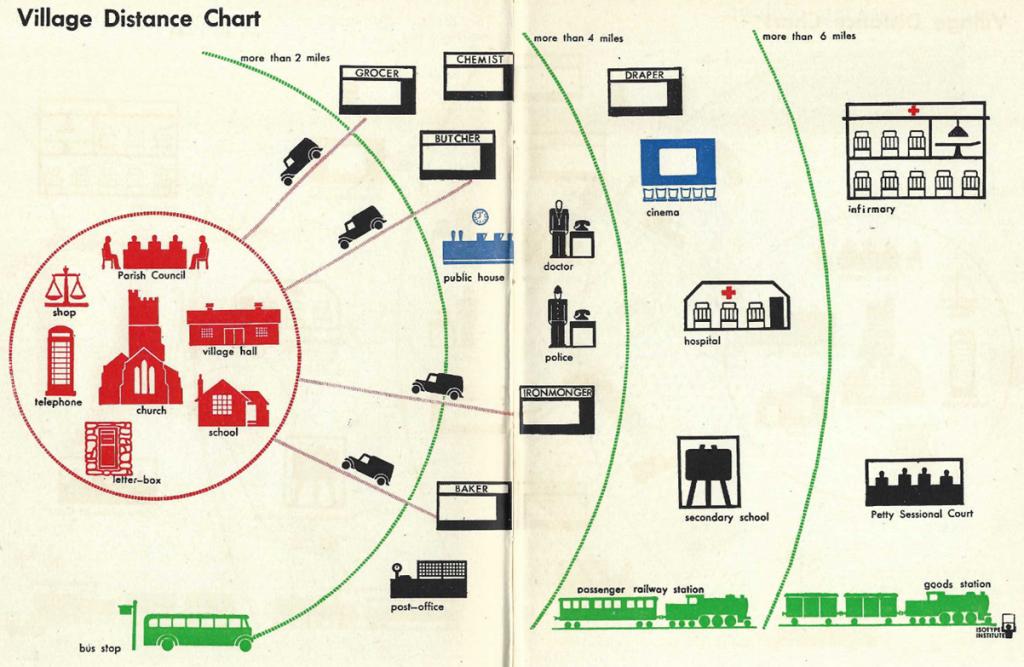

Supplementary to the text of Exmoor Village are some Isotype charts, one of which is reproduced below because it shows the services and facilities available in the area at the time.

Remarkably, although the village has lost its school and shop, the majority of the functions seen on the chart remain. Porlock has lost its police station but still has a grocer, a chemist, a butcher and an ironmonger. As far as delivery services go, Luccombe villagers will now be ordering an almost unlimited array of goods from anywhere in the world at the touch of a key, and perhaps do this more readily than they would travel the three miles to Porlock.

The greatest casualty has been the railway, which must have brought the holidaymakers who stayed in the village even if the bus was the public transport that played the greatest part in day-to-day life. The 10 buses in each direction in 1944 are now seven. The main road is one and a half miles from The Square.

Minehead Station, five miles away, closed in 1971 and the nearest network station became Taunton, 26 miles; this is not much less than the scout’s 29-mile journey from Sampford Peverell.

The nearest goods station dealing with full wagon loads was Minehead, but under the 1938 cartage arrangements for goods smalls Dunster served the Luccombe area. Today there are no public goods stations at all and the railway operates no service comparable to that of 1944.