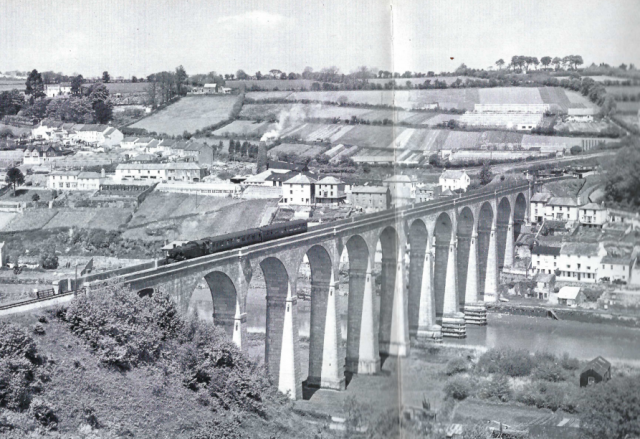

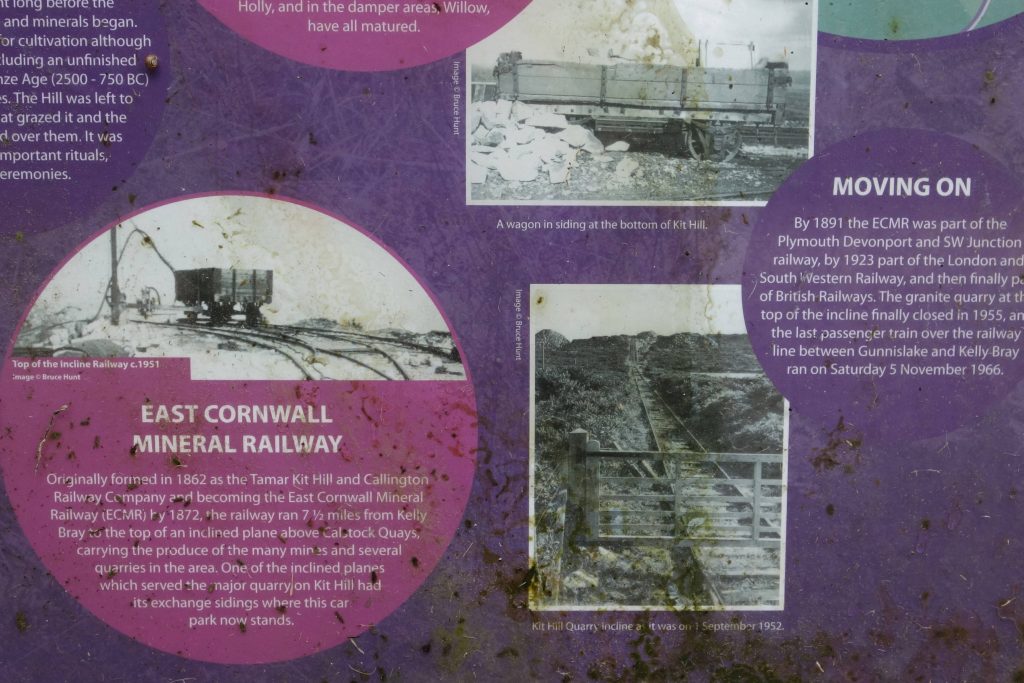

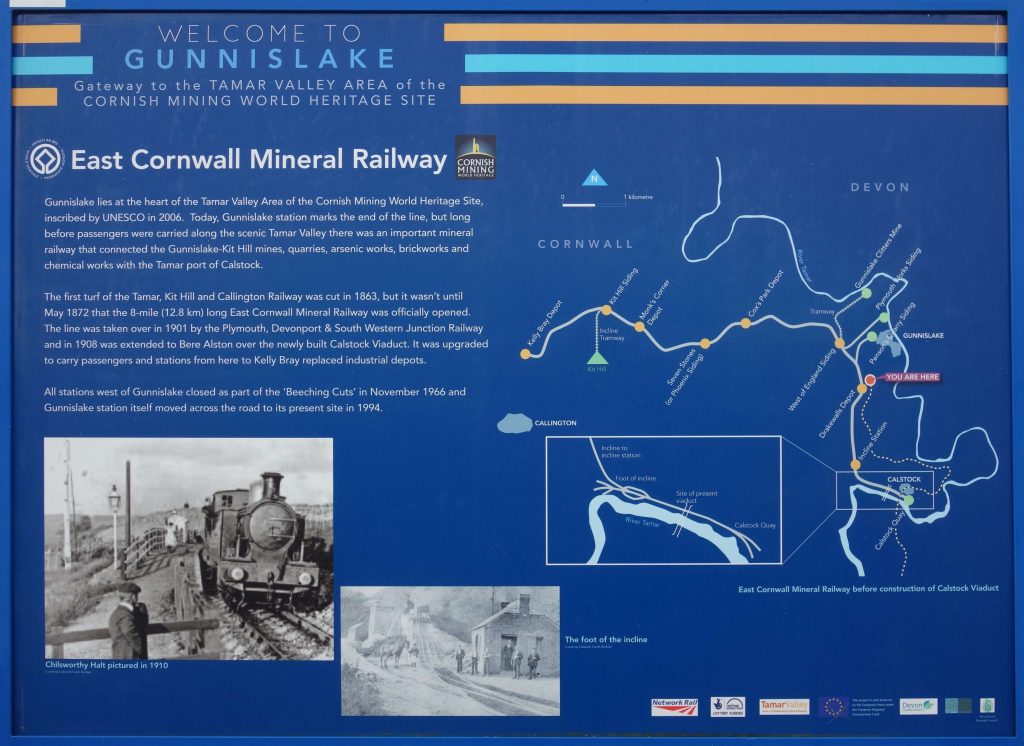

The branch began as the East Cornwall Mineral Railway in 1872, a three-foot-six gauge line from Kelly Bray to Calstock. It took over an existing rope-worked incline which served Danescoombe and the other quays on the Tamar.

In 1908, the Light Railways Act of 1896 made possible a standard gauge line from Bere Alston which took the course of the East Cornwall just south of Gunnislake.

When the main line was closed between Okehampton and Bere Alston in 1968, the section between St. Budeaux and Bere Alston became part of the branch, which in 1966 had been cut back to Gunnislake.

The scout made numerous journeys on the line from 1975, when his Mother moved to West Devon. He had remained familiar with the line but had never followed it between Calstock and Gunnislake.

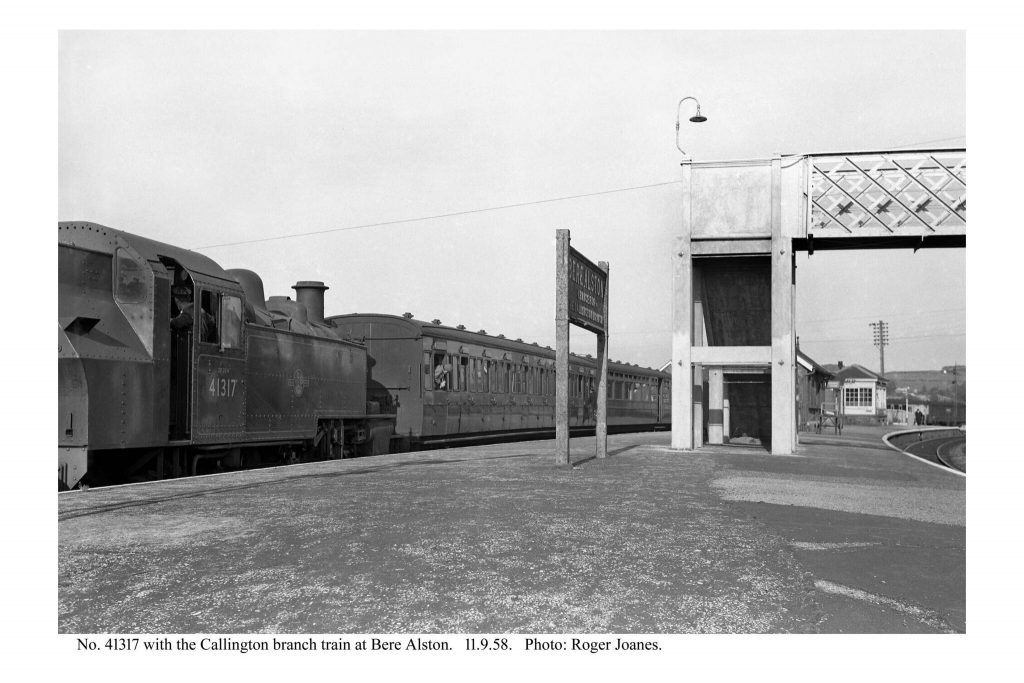

Bere Alston

Okehampton to Friary route refresher.

Calstock Viaduct

In the 1970s, the permanent way on the line was most unusual. It used short concrete sleepers—like those seen beneath the viaduct earlier—with full size wooden ones interspersed. If the scout remembers correctly, there was one wooden sleeper to every five concrete ones. These were still being used in the 1980s because the scout remembers a P.W.I. talk including mention of how the chair screw holes were replugged to prolong the life of the concrete sleepers.

The curves were so severe that the jointed track was the classic “threepenny bit” and the scout remembers sitting behind the Driver and feeling the leading bogie being repeatedly thrust sideways.

The scout once travelled on a D.M.U. which had been strengthened, perhaps for a party. The one trailer made it hard work for the four power cars.

Wagon Lift

An old boy the scout worked with remembered climbing the structure when his father, a Southern Railway Station Master, was posted at Calstock.

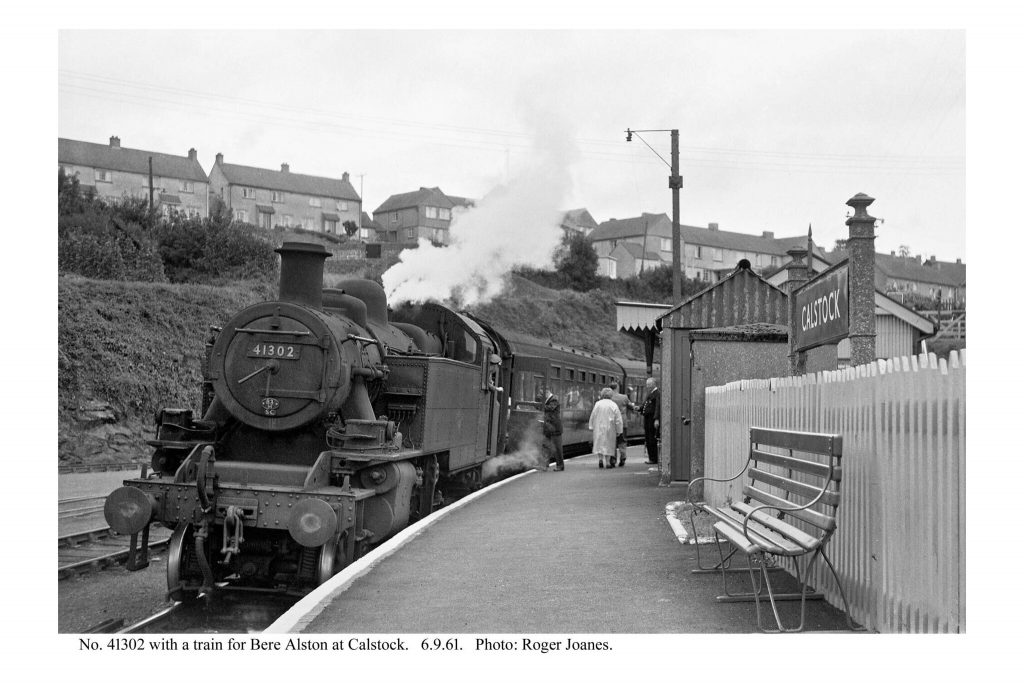

Calstock

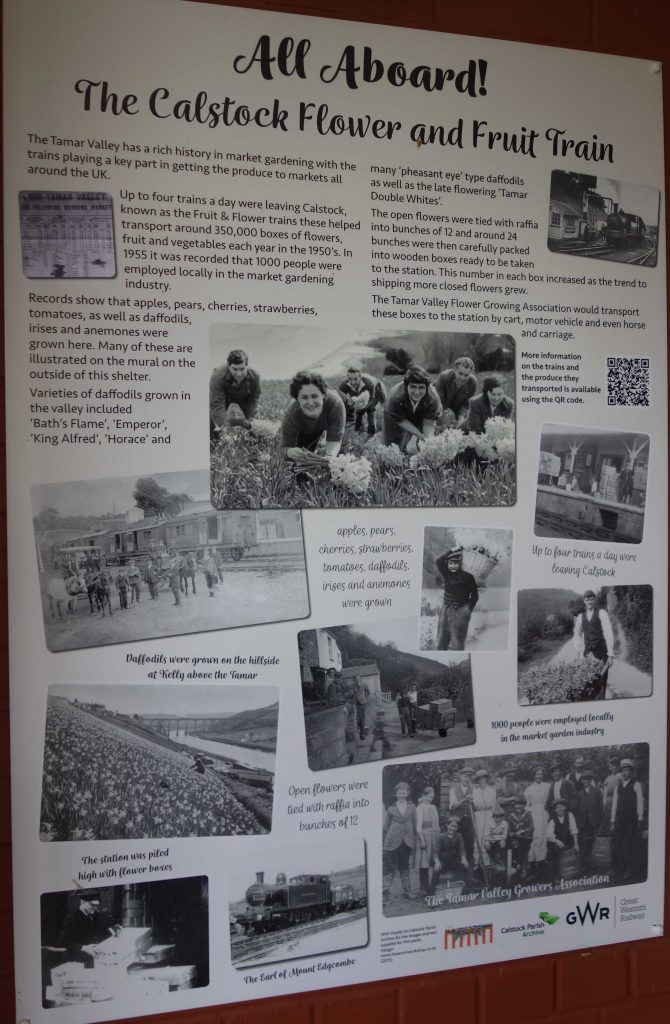

Opposite the goods yard entrance was the Chip Basket Factory, started by the Tamar Valley Growers’ Association.

The scout has a vague memory of once, when his train pulled into Calstock, seeing a mass of baskets arrayed around the old goods yard to dry in the sun. He also recalls lines of rotting wooden greenhouses on the sunny slopes beneath the line as it climbs away from the village.

The papers below refer to the factory closing in the 1960s but this Mughook post proves that it remained open: “Does anyone have any pics of the chip basket factory please? I used to work there in 1979-1981.”

Calstock Quay

The climb from Calstock is tortuous and steep. The line rises around 360 feet in three miles, which means an average gradient of 1:45.

Okeltor Crossing

Okeltor and Sandways were made “actively protected” crossings in 2024. Automatic barriers could not be installed because of the limited space and road layout. Before these improvements were completed, boards instructed train Drivers to “Stop – Whistle before proceeding.”

Sandways Crossing

Incline Station

The new line is only a few hundred yards from the summit of the old incline, which the scout photographed in 2013. He did not have time on this visit to follow the incline.

The half mile from here to the end of the line is the only bit of the East Cornwall Mineral Railway still in use.

Below, the names of the East Cornwall’s sidings or public goods depots are put in brackets, next to the later Callington Branch stations and halts.

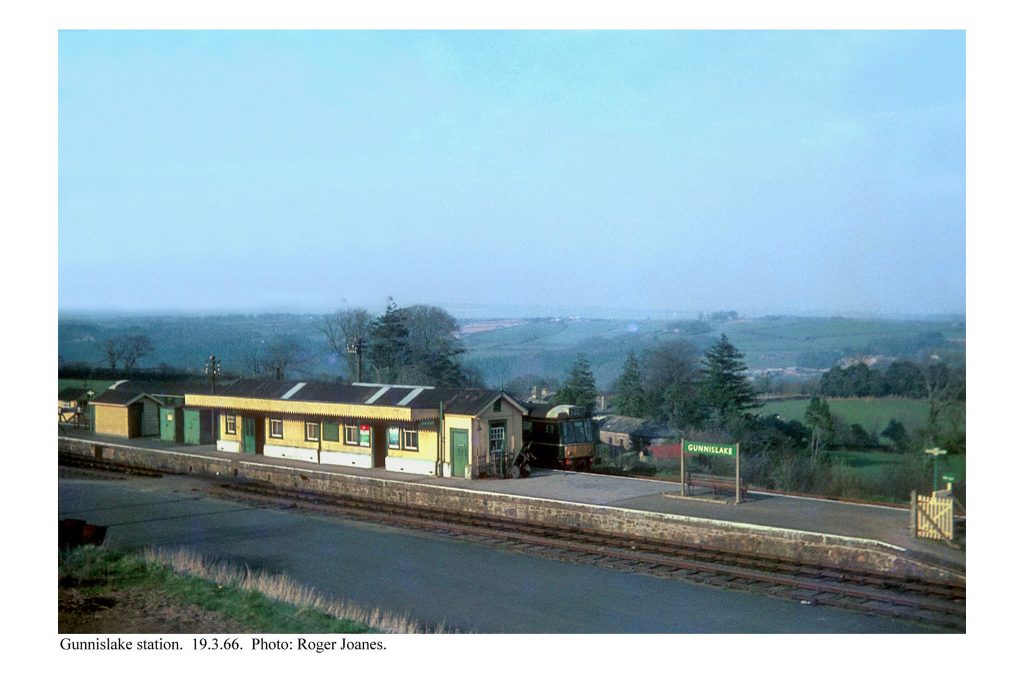

Gunnislake (1994) (Drakewalls Depot)

To avoid rebuilding the low bridge over the A390, a new station was opened on the site of the former depot in 1994. The original station was closed and the bridge demolished. After the branch was opened, Drakewalls became Perry Spear’s coalyard.

Drakewalls Mine also had a siding, just south of the depot. +

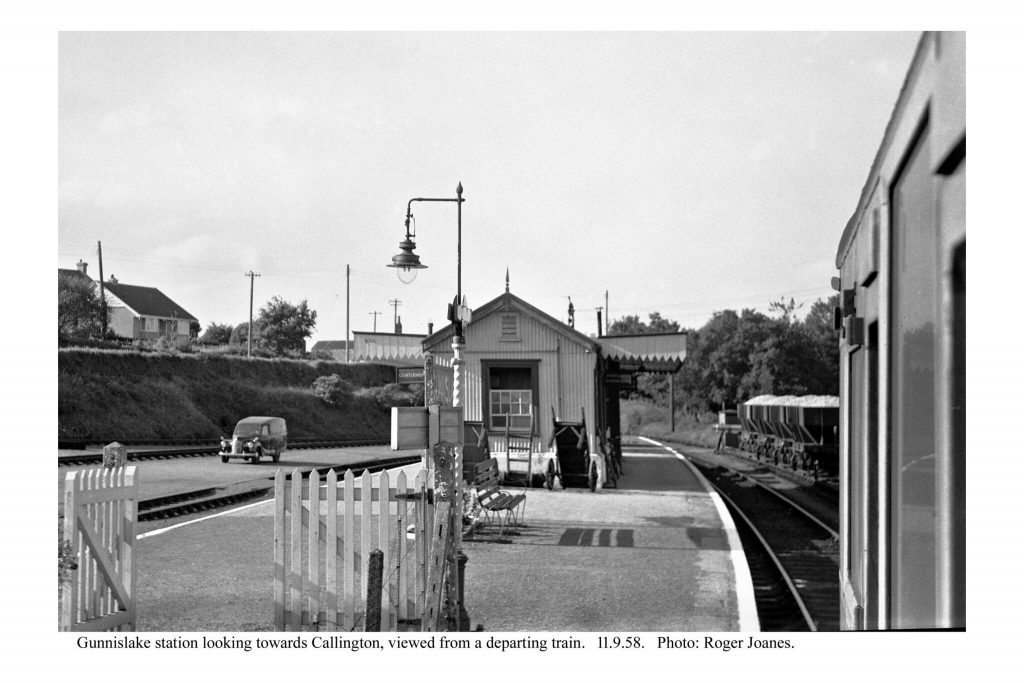

Gunnislake

The station site was disposed of at The Bristol Auction in 1996.

Copyright: Roger Joanes. Shared under Creative Commons. +

The building was still there in the late 1970s. +

Gunnislake to Plymouth in twenty seconds.

Three sidings were passed before Chilsworthy: Plymouth Works (fire brick); Greenhill Works (arsenic); and Gunnislake Clitters Mine (tin, copper and arsenic).

Chilsworthy Halt

Hingston Down Quarry

The scout took it that Whiterock Siding, which made a trailing connection with the branch just beyond Milepost Six, was laid in after Hingston Down Siding, which had a loop and was a little further along.

Latchley Halt (Cox’s Park Depot)

Sevenstones Halt (Phoenix Works)

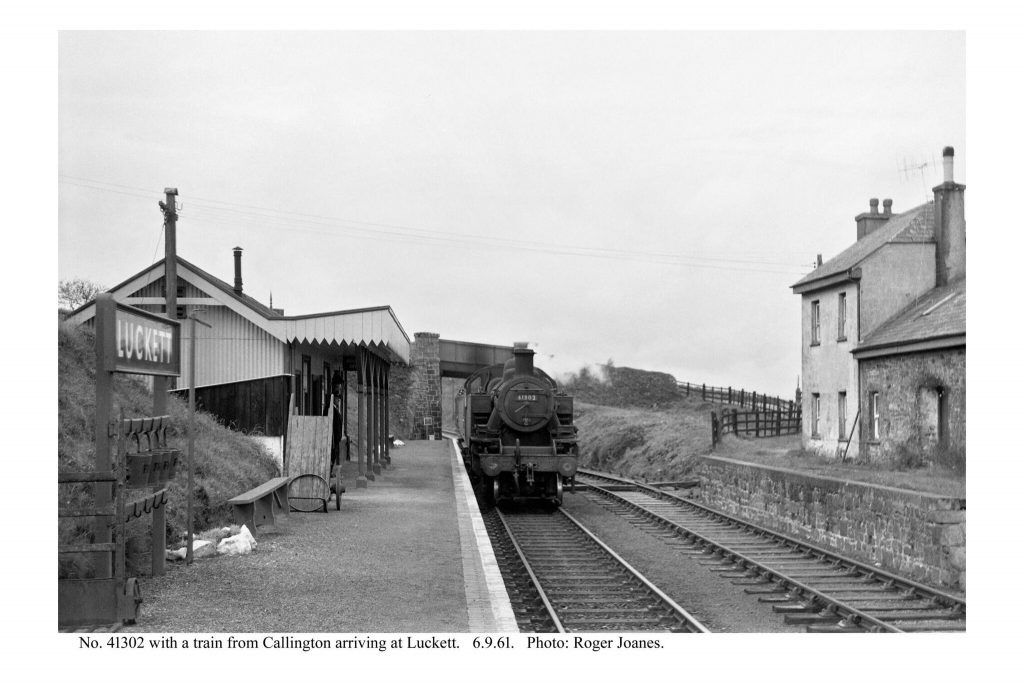

Luckett (Monk’s Park Corner)

For a year after its opening in 1908, the station was Stoke Climsland.

The fellow tending the bank asked the scout: “Railway enthusiast?” To which the scout replied: “No, professional. To distinguish myself from … ” He tailed off, thinking it best not to say what he thought of a certain fraternity.

After he’d photographed the entrance and sneered at the “waiting room” sign, he asked the fellow if he owned the place. “No, I’m just the chap who pulls the weeds,” he answered, adding: “You could speak to the owner.”

Deciding that this fellow would be more interesting, the scout chose to talk to him rather than the Airhead BnB proprietor within. He told the scout that he had never touched a computer and he produced his walkie-talkie to prove that it was only the simplest kind. He complained of people having no interest in the world around them and the scout put his usual question: “What spectacle or wonder would be sufficient of a draw to make a train passenger look up momentarily from his telescreen?”

The two could have continued but each had his task.

The short “Rover Makes Good,” produced by the Children’s Film Foundation in 1952, includes wonderful opening and closing shots of Luckett.

Kit Hill Siding

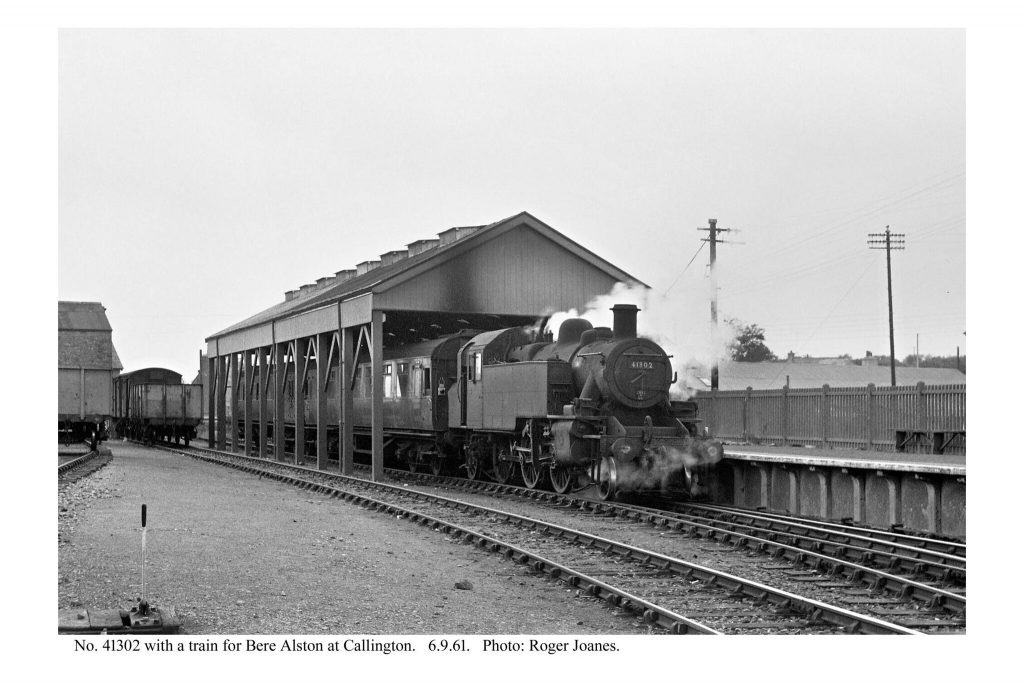

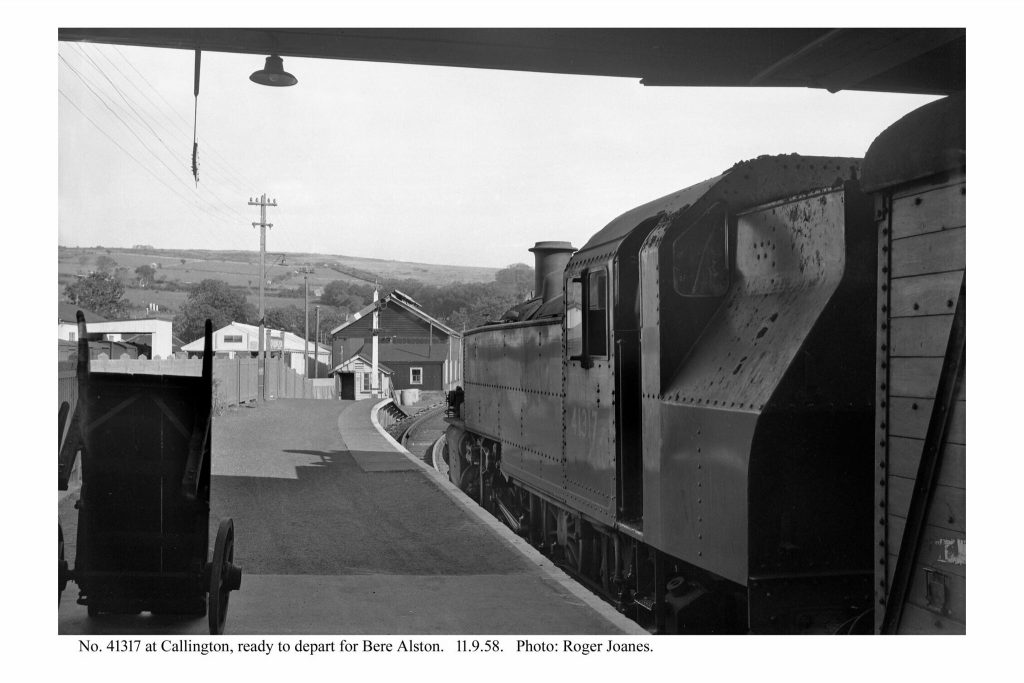

Callington (Kelly Bray Depot)

The terminus, lying at about 646 feet, was not quite the summit of the branch. Okehampton lies at 722 feet.

“All Aboard the Last Train to Callington.”

Not for the first time, when poring over turn of the century surveys, the scout had been struck by the abundance of industry in the area, much of it, of course, extractive. Only a mile from the railway, across the Tamar, lay Devon Great Consols, once the largest copper mine in Europe.

Though most mining had ceased by the early years of the 20th century, small workshops, cottage industries, producers, tradesmen, shopkeepers, farmers etc., must have supplied local needs and allowed East Cornwall to prosper, though many must have been unrewarded.

The quarries were small in comparison with today’s. A hillside has gone at Heidelburg’s Hingston Down to satisfy the hunger for tarmac and concrete aggregates, and its output has probably outstripped all the old ones and the mines put together.

The little branch railway could not easily have served this operation but it did for many years get the soft fruit and flowers to the junction so that they could be rushed to Covent Garden and other markets overnight.

The modern service economy seems to consist of everyone scratching each other’s backs and doing each other’s washing. Whereas once there were the sights and sounds of activity and function all around, now there is a pervading lifelessness. Perhaps “zero hours contracts” and “McJobs” are no worse than men being taken on and laid off, depending on the vagaries of mining, an industry by nature unsustainable.

Could the old boys who had so little of it, ever have imagined that leisure would become an industry and that feeding, accommodating and pampering the idle, the bored and the effete would one day be regular occupations?