On the sunny evening of 8th August, 1991, after attending the Okehampton Show, the scout wandered around the deserted station.

The scout returned on 22nd October the following year to photograph the A30 Okehampton Bypass, which had been opened in July, 1988.

In the railway’s “Square Deal” leaflet, published in 1996, the scout had chosen one of the photographs and let off steam.

“This is the infamous Okehampton Bypass. It is a stretch of road which I hold a special disgust for, not least because I contributed £40 [c. £140 in 2025] towards the Dartmoor Preservation Association’s £40,000 [c. £140,000 today] legal costs, which it incurred while fighting this proposed vandalism at the public enquiry.

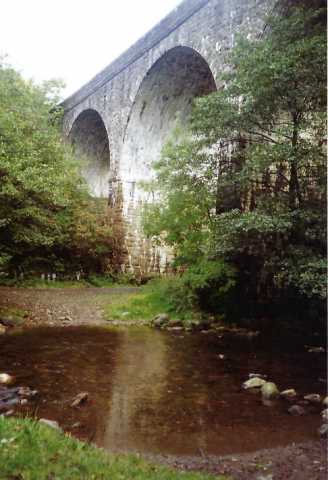

“It was photographed at midday in October, 1992. Just beyond the road is the former Southern Railway main line from Waterloo to Plymouth, now a single line mineral branch at this point. Do you see it?

“This road, like so many, was made possible by the wonderful bureaucratic device, “Cost-Benefit Analysis.” Put simply, it gives values for such things as death, injury and drivers’ time. If a life is worth £1-million, say, and it can be demonstrated that a death can be avoided by building a new road, then that is a million “benefit.” Until quite recently, environment had no value.

“The same system does not apply to railway construction. The rule is much more straightforward: it must make an 8% return on capital, something no railway has done since the earliest days. If the dual-carriageway at Okey had been subject to the pricing analysis used for railways, it would never have been built, north or south of the town.” +

Lee Waters on “Breaking Orthodoxy to Achieve Real Change,” an interview with Thomas Ableman of Freewheeling.

“You have to change the system. You have to change those D.f.T. rules around liability. You have to change it around design standards. You have to change it around cost-benefit. Once you start to unpick them and get into the details of them, these are all heavily loaded, biased formulas which have been driving us towards the same sort of approach. You look at this whole journey time savings calculation which underpins most road schemes. It gives you a positive cost-benefit return on investment but once you start to unpick—which few people bother to do—what are the weightings which underpin that and it’s complete bollocks. You know, the idea that a road scheme will save on average one minute for every person who uses it and therefore each person will be more productive and by “x,” and then you multiply that by the number of people who use that road every year and you multiply it again by thirty, because that’s the length of a road scheme in economic terms, and you come up with a figure that this road scheme is going to benefit the economy by “x”-million or -billion and it just doesn’t withstand intellectual scrutiny because, “a” it doesn’t take into account any of the other variables, the other costs, the cost of keeping on doing what we are doing, but also it assumes that every passenger is going to have a productive economic benefit from one minute and it’s just not true. But we never question that, so some poor transport minister comes along, gets a piece of advice from their officials saying “we’ve done the numbers on this road and it’s going to benefit the economy by twenty billion and it’s going to create these number of jobs in building it and it’s going to ease this congestion,” they don’t then go back and check that. One of the schemes we cancelled in North Wales, the Flintshire Red Route, it’s own business case, which hadn’t been published and was not publicly known, the roads review unpicked it and showed that even its own roads business case showed that the road was going to be back to its current level of congestion within fifteen years so you are spending £400-million destroying ancient woodland, using enormous amounts of embodied carbon on a scheme that’s going to be back to current congestion levels within fifteen years and the opportunity cost of using all that money on that scheme that could’ve improved things in a more sustainable way that was a debate and a comparison that was never had. So we really do need to be far more critical in our thinking of some of the assumptions that underpin s lot of these decisions.”

Lee Waters is a former Transport Minister in the Welsh Governnment.

“It is now the policy of Government that investment in trunk roads should be directed to developing routes for long distance traffic which avoid National Parks and that no new road for long-distance traffic should be constructed through a National Park, or existing road upgraded, unless it has been demonstrated that there is a compelling need which would not be met by any reasonable alternative means.”

Department of the Environment Circular 4/76 (para. 58) Report of the National Park Policies Review Committee, 12th January, 1976

Thirty years after this sacrilege was committed, when work to reinstate the passenger service to Okehampton began, along an existing route which had never become entirely disused, the railway was burdened with the whole weight of new environmental crapspeak, enforced by wildlife “commissars” who shadowed every P.-Way man, lest he disturb a dormouse or a newt; or any flora and fauna that had found a haven from the devastation caused in large measure by motor traffic.

Network Rail was forbidden to do any more than trim branches, even as a fortune was being spent on re-laying the line, with new ballast which would quickly become choked by leaf fall. When the linear nature reserve was handed to the operator, it was actually not safe for the passage of trains at the permitted line speed. The following season, foliage was brushing the carriages and every autumn and winter there has been disruption caused by falling trees.

The scribe wrote this in a letter to the Devon County transport supremo in 2016:

“Though an imposition, the turnpikes were built without much difficulty. These and other roads were greatly improved for motor traffic from the 1920s to the ’50s. There followed the era of massive new road construction which was supposed to render the railways redundant. None of this, certainly up to the 1970s, had to face the environmental and economic hindrance now slowing even the simplest railway reinstatement or infrastructure project.

“If we accept that the railway is being called upon to relieve the excesses set in motion by unbridled road expansion, then surely there is justification for some derogations and easements to allow railway schemes to be hastened. Instead of saddling them with a weight of legislation that the competition never had to bear, and which is only possible because of the surfeit of graduates that write the largely meaningless reports and conduct the pointless studies, should it not be enough to show that the alternative would be even more growth in traffic and road space? I know that this is a matter for central government and local authorities must obey the law. Nevertheless, it is human life I am talking about, not a game of chess or a table-top exercise designed to bog down progress. Is it not time for the counties to press for a relaxation of diktats in order better to meet government targets?”

The utilicon departed Teign Valley Depot at 0825. A near two-hour stop at Sticklepath may have allowed the scout to visit Finch Foundry. He also called at North Road Industrial Estate. After standing at the station between 1151 and 1310, the utilicon stopped in the town and at Meldon Quarry A single rail and a buffer-coupler were collected from Merrivale Quarry and the utilicon returned to Christow at 1658. Warren House was passed at 16/16½.